Recommendation: Begin inverted-flight exploration in a maiden aerobatic airframe under certified instructor supervision, and never attempt such maneuvers in a standard transport machine. This keeps the learning curve aligned with the design envelope and protects the operator from unexpected failures. A controlled environment in the factory training area ensures that shifts in weight and fuel distribution remain within safe limits.

In inverted attitude, the wing must generate lift with a careful balance of angle of attack and thrust. The pilot must apply a deliberate control input to preserve a stable flight path; aerobatic shapes optimize the lift curve and maintain control authority across g-loads that typical transports cannot sustain. The diameter of the tail surfaces and wing planform influence yaw and roll damping, and the floor-level center of gravity range becomes crucial for stability during the maneuver.

To put numbers on it, compare the performance envelopes of ordinary airliners with those of dedicated aerobatic platforms. In the maiden tests, the factory logs show that many aerobatic types are certified for roughly +/-9 g, with inverted operation feasible for tens of seconds or more depending on fuel-system design. The a3xx reference platform illustrates how an airframe designed for passenger service can incorporate a limited inverted-feed arrangement in a dedicated prototype; theres a distinctive line between what can be done briefly and what must be avoided as fatigue and lubrication issues accumulate. Diameter of the propeller and wing-area ratio influence the speed and reliability of transitions, so operators rely on those details to plan safe rehearsals.

During training, keri sensors track pitch and roll with high fidelity, and the data pieces speak to a robust statement about feasibility. Upstairs simulators let crews rehearse routines before stepping into the floor-mounted controls; details from each flight are stored, cross-checked, and used to refine the performance envelope. Resorts near airfields sometimes host exhibitions where pilots demonstrate controlled inverted entries under strict supervision; the resulted understanding helps every operator align mission requirements with safety margins.

Upside-Down Flight: Practical Aerodynamics and Engine Response

Only operate inverted under approved profiles and with trained teams; therefore, do not attempt outside supervised programs. Preflight checks must confirm fuel and oil systems support inverted attitude, and the center-of-gravity remains within edge margins. This approach reduces the risk of fuel starvation and oil surge during rotation and recovery.

Engine response depends on fuel delivery and oil management. Inverted attitude may trigger fuel-pressure fluctuations and potentially lean or rich mixtures as feed lines change orientation. Many engines tolerate short inverted intervals, but pilots must monitor RPM and fuel pressure. Sometimes, feed lines trap air and cause pressure dips. Ensure powered fuel pumps are selected for the scenario and that lines are routed to avoid air pockets; earlier checks of system orientation help prevent interruptions.

Loads increase on the wing’s lower surface during inverted phases, edging toward stall margins and reducing control effectiveness. Longer inverted times raise peak loads and heat bearings; therefore pilots should plan recovery points and avoid prolonged segments. After inversion, perform checks for leaks, temperature rise, and sensor consistency; with disciplined practice, handling becomes almost routine.

Practical operations in traffic scenarios require coordination with large hubs and government oversight. Many incidents lead to tightened training; development programs in regions such as qatar call for rigorous procedures. Teams will, therefore, stay conservative and forever vigilant, and call for ongoing evaluation; further, after each session, data should be collected and shared to drive responsible improvements.

| Condition | Engine RPM | Fuel Pressure | Oil Pressure | Notes |

| Upright baseline | ~100% | Normal | Normal | Nominal operation |

| Inverted, short duration | ~95-100% | Fluctuating | Normal | Short inverted interval; monitor |

| Inverted, extended | ~90-95% | Possible pressure drop | Low if not managed | Extended inversion; not recommended |

Lift behavior in inverted attitude: AoA, camber, and load distribution

Recommendation: set a small negative angle of attack for inverted operation, favor a cambered profile to generate meaningful lift with controlled drag, and verify through rigorous tests and strain analysis to ensure the wing-root and joints remain within land safety margins. Stop any test if stress exceeds limits; use evacuation drills and high-fidelity simulators to validate performance before actual flight, and build repertoires that align with industry standards.

-

AoA in inverted attitude

The angle between the wing’s chord line and the relative wind is reversed in inverted flight. To generate useful lift, aim for a modest negative AoA that stays inside the airfoil’s linear lift region. In practice, a cambered profile tolerates -2° to -6° AoA more gracefully than a symmetric section; speeds and Reynolds numbers shift the exact value. The result is a stable lift contribution that supports weight without excessive drag, meaning the aircraft remains controllable along airways or during a controlled descent to land.

-

Camber and lift characteristics

Cambered airfoils convert a portion of negative AoA into upward force in inverted attitude, while symmetric sections require substantially larger negative AoA and incur higher drag. Those differences matter for maneuver margins and for the expected energy state during approach and landing. Generating lift with inverted attitude is easier with a moderate camber, but care is needed to avoid early stall and excessive pitching moments, which can complicate control in tight airspace.

-

Load distribution and structural stress

Lift distribution across the span remains a primary determinant of root bending and torsional loads, but orientation shifts how those loads transfer to the fuselage and landing gear. In inverted attitude, root moments often rise relative to upright conditions, increasing stress in the upper skin and primary spars. The difference shows up in unloaded versus loaded configurations: with no payload, margins are larger; with a single pilot or a heavy payload, margins tighten. For the industry, this underscores the need for rigorous design checks, including strain tests and finite-element analysis, to ensure the land system and wing-box can absorb inverted-load cycles without fatigue.

-

Validation, tests, and practical guidance

Tests should cover a range of speeds and air densities, including high-speed cruise and low-speed handling. Use a combination of wind-tunnel data, computational models, and full-scale measurements to build a reliable inverted-lift map. If any test indicates stress approaching limits, stop and reassess the airfoil choice, thickness distribution, or reinforcement at the root. Section-by-section verification helps isolate loads and verify mean load paths under unloaded and loaded states, so actual flight margins match the designed safety envelope.

-

Industry context and examples

In modern airworthiness practice, operators build suites of simulations and flight-tests to reflect real-world conditions. Large carriers, including qantas, routinely integrate inverted-performance data into training and maintenance planning, with dedicated building and testing facilities that resemble hotels and other controlled environments for crew training in evacuation procedures. Those procedures rely on robust lifting behavior during inverted attitudes to maintain stability, visibility, and control–a meaningful difference that actually affects overall safety and profit margins. Alex, an engineer in the field, notes that such rigorous validation translates into safer landings and more predictable handling, especially during unexpected maneuvering or go-arounds.

-

Key takeaways for application

- Choose a cambered airfoil for inverted lift reliability and manageable drag.

- Keep AoA within a modest negative range to maintain positive lift without overloading structure.

- Assess load distribution carefully, focusing on root bending and torsion under inverted loads.

- Validate through rigorous tests and measurements; stop tests that threaten structural integrity.

- Translate findings into training, maintenance, and safety documentation to support industry operations and airways planning.

- Use real-world case studies and simulations from modern fleets to tighten the link between theory and practice.

Wing geometry and control surfaces that support inverted flight

Begin with a symmetrical airfoil, keep washout mild, and add anhedral tips to preserve roll control when the wing is inverted. This setup maximizes lift distribution and elevator authority at altitude, while reducing tip stall risk. Use a moderately tapered planform and a robust wing spar to deliver a stone-solid structure that tolerates stress without excessive weight.

Choose a wing with a compact span and a sensible aspect ratio to balance maneuverability and stability in inverted regimes. A strutless, clean surface minimizes drag and helps maintain consistent control feel across areas of operation. Ensure the root-to-tip twist favors uniform loading so the center of lift remains near the CG during inverted attitudes, preventing sudden pitch change points that can surprise the pilot. Those design choices help keep the airfoil within the optimal range to maximize your score for controllability and handling, especially when altitude changes are rapid.

Control surfaces should be oversized relative to a conventional upright configuration: full-length ailerons split into inboard/outboard sections, servo-balanced to prevent flutter, and backed by spoilers or spoilerons for rapid roll damping at high AoA. Elevators must retain authority in negative-G contexts, so use a robust tailplane with independent trim and a lockable stabilizer to avoid trim drift during inverted flight. Use a flight control system that maintains consistent control law across attitudes, and ensure the control surfaces remain effective when the wing is upside down, a key factor in maintaining a stable arc and avoiding damage from unexpected loads.

From a manufacture and structure standpoint, select materials with high stiffness-to-weight ratios (composites or advanced alloys) and design wing joints to resist asymmetric loads. Reinforce the wing root and spar caps to handle repeated inverted cycles; implement redundancy in critical actuators and a ballast plan that prevents CG drift between configurations. In October announcements in England, manufacturers highlighted enhanced procedures for testing inverted configurations in hangars and wind tunnels, stressing proper maintenance and inspection cycles to prevent hidden damage and to keep mass properties within limit. Those steps support long-term reliability and minimize stone-hard fatigue over time.

Operationally, develop a step-by-step inverted-flight procedures manual that covers preflight checks for control surface alignment, trim accuracy, and sensor calibration. Use altitude simulations to verify elevator authority at various loads, and perform incremental test points to verify stall margin and loss of lift symmetry when inverted. Maintain a careful log of wear on hinges, balance weights, and surface gaps; this helps ensure smaller tolerances don’t become a vulnerability and reduces the risk of damage during routine taxi tests in hangars or on ramps. Youve got to balance max performance with safety, and, when executed correctly, the geometry and surfaces that support inverted attitudes deliver great responsiveness without compromising overall handling. Shutterstock imagery and real-world test data points can help verify expected behavior in those areas and provide a clear point of reference for engineers and pilots alike. Restaurants and maintenance crews focused on reliability will appreciate the predictable response and the ability to keep the aircraft within prescribed limits during routine procedures. The goal is a reliable, repeatable inverted envelope that enhances the airliner-class stability mindset while preserving mass efficiency and structural integrity.

Stall dynamics and recovery tips during inverted maneuvers

Push forward on the control to reduce the wing’s angle of attack, roll toward wings level, and smoothly add thrust to restore airspeed; target a margin of roughly 10-15 knots above the inverted stall speed for the configured setup.

In inverted flight the wing continues to stall at a critical angle relative to the oncoming air, so onset can be abrupt if energy fades or gusts strike. Gravity and yaw interplay with the airframe, making coordinated recovery essential: maintain smooth control, avoid overreaction, and reestablish a safe energy state before returning to straight and level flight.

Data snapshots for common configurations: light singles in clean configuration show upright stall around 40-60 knots, while inverted stall speeds are typically within a small margin of those values when weight and thrust are balanced; with heavy loading or flap settings the margin widens. Expect control feel to pulse near the threshold; always align with the configured performance envelope and compare margins across configurations, including factors observed by others in the fleet.

Practical takeaways for crews, operator teams, and customers: responsible training across companies and etihads networks must emphasize nonstop practice of inverted stalls in simulators and in-flight to keep exits clear and people safe. The declared goal is a safe future where hi-fly programs ensure robust thrust and power margins, protecting the living safety culture on board so every passenger and crew member has a savior option if an unusual attitude occurs. Manage the situation with a calm, measured sequence: reduce AoA, roll to wings level, gently apply power, and verify necessary airspeed before resuming flight. In addition, ensure clear exits for every person on board and keep evacuation routes ready for an orderly response if needed. For evacuation planning, maintain clear paths to exits and ensure crew can assist each passenger if a scenario requires cabin securing or evacuation.

Engine thrust, fuel flow, and lubrication when aircraft is inverted

Install a dry-sump lubrication system with inverted pickups and a dedicated header tank sized for inverted segments. Maintain oil pressure at 60–75 psi at full power; keep a minimum of 30 psi during inverted maneuvers. Route scavenging lines to avoid air ingestion and install crankcase baffles to prevent oil pooling. This arrangement makes continuous lubrication inflight during inverted attitudes reliable and provides enough reserve for short sequences.

Fuel delivery requires flop tubes and a header tank that keeps the engine fed during a 90-degree inverted turn. Use a header capacity of 1–3 US gallons (4–11 L), sized to cover typical aerobatic sequences; main pump plus electric boost pump should deliver 40–60 psi to rails. Install a non-return valve to stop siphoning when inverted; route lines away from hot surfaces and maintain distance from exhaust to reduce vapor lock and heat soak.

Thrust behavior under inversion varies by propulsion type. Jet engines retain near-rated thrust, but intake pressure can drop at higher angles and mach values, affecting peak power. For prop-driven airframes, propeller wash interacts with wing airfoils, altering loads on the airfoils and changing pitch moments. Align the thrust line near the wing’s center of gravity to minimize adverse moments; advances announced by France‑based manufacturers introduced inverted-ops improvements that look to stabilize response through the entire maneuver envelope.

Operational guidance emphasizes deliberate sequencing. During inflight practice, stop extended inverted exposure if oil or fuel pressures depart from limits; use a private instructor to work through qualifying sequences and build tolerance for load changes. Plan around crew alerts and rest, ensuring there is space to recover between high-demand passes; the discipline reduces risk and improves predictability so the flight deck stays focused rather than chasing readings.

Maintenance and testing should verify all paths. In December, perform ground checks of the inverted lubrication and fuel systems, using fiber-optic sensors to monitor oil temperature, pressure, and line conditions. Found data should show stable loads and no cavitation in scavenger lines; there is enough margin to support repeated inflight inverted segments. There are pieces of the system that must be weighed against mission needs, with credits earned for consistency across varied weather and airspace. Space is allocated for extended tests to confirm reliability under busy schedules and space constraints on fleet types; actually, careful recording of results helps build a stronger baseline for future upgrades and more robust operation there.

Pilot workload and instrumentation layout for upside-down operation

Implement inverted-flight readiness by using a mirrored primary flight display (PFD) and navigation display (ND) with a fixed horizon, plus large attitude, airspeed, and altitude readouts; keep essential data within the captain’s line of sight so motion cues are intuitive and comfortably interpreted when the aircraft assumes inverted attitude.

Configure the cockpit so the captain’s data cluster remains the primary source during inverted operations, while a secondary data set mirrors the captain’s data for redundancy. A similar set should be available on the first officer’s side. Engine and systems health, fuel, and configuration data should live on a reinforced edge panel that stays legible as the view tilts; ensure a robust standby attitude indicator and altimeter are positioned for quick glance without reorienting the head. After transitions, pilots spend less time scanning and more time monitoring automation.

Controls should be reachable with the same hand during inverted flight; adopt a fixed yoke or a grip-hinged control that remains intuitive when the view is inverted. Provide redundant power to displays and a ballast-independent electrical bus to prevent loss of critical data in motion; include an inverted-mode toggle that privileges essential alerts. Therefore, hardware must be unique and robust, minimizing challenges and damage risk and preserving crew authority.

Data density must be managed by a data rectangle around the edge of the PFD to reduce eye travel; the diameter of digits on the speed and altitude readouts should be large enough for legibility at any attitude; use high-contrast colors and anti-glare coatings to keep information readable when the aircraft banks or inverts. Provide a version of the aeroreport that summarizes engine health and air data in inverted flight, with options for baseline and reinforced configurations. Easy to read, easier to manage for pilots, easier for maintenance.

Operational procedures should include simulated inverted sessions on a quarterly basis, with debriefs in crew lounges to capture lessons on workload and readability. In long-range wide-body four-engine operations, passenger comfort matters: limit cockpit noise and vibration, coordinate on-sky clearances, and ensure sleep opportunities for crew between high-workload segments. After each inverted event, review data to identify changes that could reduce motion stress and improve response times.

Cost and maintenance notes: upgrading instrumentation and redundancy in a four-engine, wide-body fleet is expensive, but the payoff is lower non-normal incident risk and better crew endurance. Reinforced seating and restraint systems, plus non-destructive edge-mounted annunciators, reduce potential damage during inverted operations. Operators should publish a clear set of options for inverted readiness, including baseline, reinforced, and unique modular versions; collect aeroreport-style metrics to track workload and response times, and adjust training accordingly.

Demystifying Aerodynamics – Can Planes Fly Upside Down?">

Demystifying Aerodynamics – Can Planes Fly Upside Down?">

JetBlue Launches Summer Seasonal Service from Boston to Asheville">

JetBlue Launches Summer Seasonal Service from Boston to Asheville">

Where to Stay in Christchurch – The Best Neighborhoods for Your Visit">

Where to Stay in Christchurch – The Best Neighborhoods for Your Visit">

How to Buy Artwork from a Gallery – A Step-by-Step Guide">

How to Buy Artwork from a Gallery – A Step-by-Step Guide">

Castle Hot Springs – What It’s Like to Stay at One of Arizona’s Most Exclusive Luxury Resorts">

Castle Hot Springs – What It’s Like to Stay at One of Arizona’s Most Exclusive Luxury Resorts">

Carnival World Mastercard 2025 – Is It Worth It? Here’s the Breakdown">

Carnival World Mastercard 2025 – Is It Worth It? Here’s the Breakdown">

How to Use Points to Upgrade Cash Flights – The Complete Guide">

How to Use Points to Upgrade Cash Flights – The Complete Guide">

Do I Avoid APR If I Pay on Time? A Clear Guide to Credit Card Interest and On-Time Payments">

Do I Avoid APR If I Pay on Time? A Clear Guide to Credit Card Interest and On-Time Payments">

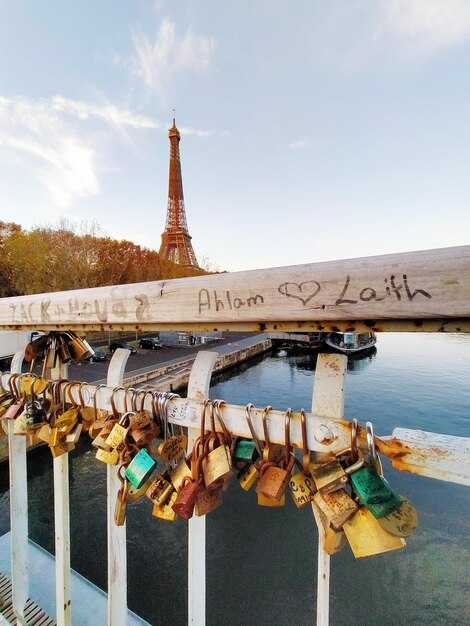

48 Hours of Luxury in Paris – The Pursuitist Passport Weekend Guide">

48 Hours of Luxury in Paris – The Pursuitist Passport Weekend Guide">

Hummsafar Participant Publication – Latest News and Updates">

Hummsafar Participant Publication – Latest News and Updates">

11 Essential Stats for the French Riviera Property Market in 2025">

11 Essential Stats for the French Riviera Property Market in 2025">